Ethical issues in research involving human participants

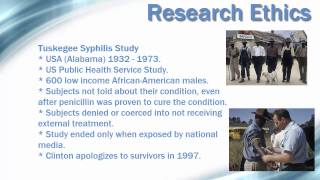

Please enable it in order to use the full functionality of our / practice management / in ethics: protection of human in ethics statements: hed 2014. This issues in ethics statement is a revision of protection of human subjects (2005) and has been updated to make any references to the code of ethics consistent with the code of ethics (2010r). The board of ethics reviews issues in ethics statements periodically to ensure that they meet the needs of the professions and are consistent with asha in ethics statements: time to time, the board of ethics determines that members and certificate holders can benefit from additional analysis and instruction concerning a specific issue of ethical conduct. They are illustrative of the code of ethics (2010r) and intended to promote thoughtful consideration of ethical issues. The facts and circumstances surrounding a matter of concern will determine whether the activity is conduct of research and scholarly activities is critical to the development of the professions, clinical practice, and basic scientific knowledge in speech, language, and hearing processes. Principle of ethics i, rule p, states: "individuals shall enroll and include persons as participants in research or teaching demonstrations only if their participation is voluntary, without coercion, and with their informed consent. A basis for this rule is embodied by ethical principles that guide the participation of human subjects in biomedical research. The key components of informed consent revolve around three principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and an historical perspective, ethical issues underlying informed consent are addressed in three internationally recognized documents. In 1947, the nazi war crimes tribunal issued the first internationally recognized code of research ethics, the nuremberg code (1947; jama, 276, 30, nov. In 1964, members of the 18th world medical assembly, which was held in helsinki, finland, established formal recommendations to guide physicians in biomedical research involving human participants, the declaration of helsinki (world medical organization, 1964; british medical journal 313, 7070, dec. 93-348) and established the national commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral research. In the course of its deliberations over a four-year period, the commission developed the foundation of ethical principles for human research participants, the belmont report (1978: dhew publication no. This prompted the establishment of institutional review boards (irb) at the local level to review and approve all federally funded research and is now required by the department of health and human services (dhhs). Although members and certificate holders engage in research activities as a part of their professional responsibility, they may not be in settings that require approval of an irb for the conduct of such activities. Nevertheless, they must resolve ethical issues to protect the involvement of human participants in research activities. Individuals in this situation who are unfamiliar with protection of human participants during research activities may choose to contact asha's research office for health insurance portability and accountability act of 1996 (hipaa) provides additional guidance to researchers who provide treatment to research participants. With a compliance date of april 14, 2003, the rule requires that prior to the use or disclosure of protected health information, researchers who are covered entities under hipaa must receive authorization from research participants. Although there are exceptions to these provisions, the intent of the rule is to assure the privacy of information collected as part of most human research activities. Waiver of these provisions can be obtained by an irb or privacy board that conforms to the general structure outlined in the common rule (national institutes of health, office for protection from research risks, part 46, protection of human subjects, subpart a) which supercedes the research provisions of key components of informed consent, tenets defined by the 1979 belmont report, are:Respect for persons. Persons participating in research should be fully informed about the research activity and given the respect, time, and opportunity needed to make a personal decision to participate. The gains or benefit from the research must be greater than any potential harm to human participants. The persons who are given the opportunity to participate and bear the risk of possible harm should also receive the benefits of the ement of human participants in research activities may take many forms. In addition to large-scale clinical efficacy or medical studies, research activities may include pilot projects, case studies, and student or course projects. Approval for the research activity should be sought from the local irb if one is in place. Members and certificate holders should evaluate the research activity with respect to the basic tenets of the 1979 belmont report, and should document the procedures employed to adhere to these t for persons. Participants should be treated as autonomous agents and no pressure should be used or implied to encourage participation. Furthermore, participants should be given the opportunity to decide to withdraw from participation at any time, without prejudice or penalty. Special consideration must be taken when interacting with participants who may be incapable of understanding information to make a fully informed decision about research. To secure the well-being of all research participants, every action must be taken to protect them from harm and ensure that they experience the possible benefit from participating in the research. In addition, stimuli for use in research should be scrutinized for possible vocabulary or concepts that may offend e. Every effort should be made to distribute the risks and benefits fairly and without bias, therefore the decision about whom to include or exclude in a research activity is sensitive.

Ethical issues in psychological research with human participants

Equal opportunity for participation should be provided, independent of race, socioeconomic status, or education, unless it is justified by the objectives of the research activity. Informed consent involves the knowledge of the potential risks inherent in participating in research and what personal or general benefits, if any, may be gained by participating. Nbac’s functions are defined as follows:A) nbac shall provide advice and make recommendations to the national science and technology council and to other appropriate government entities regarding the following matters:1) the appropriateness of departmental, agency, or other governmental programs, policies, assignments, missions, guidelines, and regulations as they relate to bioethical issues arising from research on human biology and behavior; and 2) applications, including the clinical applications, of that research. Nbac shall identify broad principles to govern the ethical conduct of research, citing specific projects only as illustrations for such principles. In addition to responding to requests for advice and recommendations from the national science and technology council, nbac also may accept suggestions of issues for consideration from both the congress and the public. Nbac also may identify other bioethical issues for the purpose of providing advice and recommendations, subject to the approval of the national science and technology al bioethics advisory commission. Provost emerita, dean emerita, and lucille cole professor of nursing university of michigan ann arbor, research and policy ment of child and adolescent psychiatry columbia university new york, new w. Quinlan, office manager sherrie senior, ting research participants—a time for ting the rights and welfare of those who volunteer to participate in research is a fundamental tenet of ethical research. A great deal of progress has been made in recent decades in changing the culture of research to incorporate more fully this ethical responsibility into protocol design and implementation. In the 1960s and 1970s, a series of scandals concerning social science research and medical research conducted with the sick and the illiterate underlined the need to systematically and rigorously protect individuals in research (beecher 1966; faden and beauchamp 1986; jones 1981; katz 1972; tuskegee syphilis study ad hoc advisory panel 1973). It is a patchwork arrangement associated with the receipt of federal research funding or the regulatory review and approval of new drugs and devices. In addition, it depends on the voluntary cooperation of investigators, research institutions, and professional societies across a wide array of research disciplines. Increasingly, the current system is being viewed as uneven in its ability to simultaneously protect the rights and welfare of research participants and promote ethically responsible ch involving human participants has become a vast academic and commercial activity, but this country’s system for the protection of human participants has not kept pace with that growth. On the one hand, the system is too narrow in scope to protect all participants, while on the other hand, it is often so unnecessarily bureaucratic that it stifles responsible research. Although some reforms by particular federal agencies and professional under way,1 it will take the efforts of both the executive and legislative branches of government to put in place a streamlined, effective, responsive, and comprehensive system that achieves the protection of all human participants and encourages ethically responsible y, scientific investigation has extended and enhanced the quality of life and increased our understanding of ourselves, our relationships with others, and the natural world. Nonetheless, the prospect of gaining such valuable scientific knowledge need not and should not be pursued at the expense of human rights or human dignity. The 1974 formation of the national commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral research and the activities in the early 1980s of the president’s commission for the study of ethical problems in medicine and biomedical and behavioral research, american leaders have consistently tried to enhance the protections for human research participants. The research community has, in large part, supported the two essential protections for human participants: independent review of research to assess risks and potential benefits and an opportunity for people to voluntarily and knowledgeably decide whether to participate in a particular research charter of the national bioethics advisory commission (nbac), a presidential commission created in 1995, makes clear the commission’s focus: “as a first priority, nbac shall direct its attention to consideration of protection of the rights and welfare of human research subjects. In our first five years, we focused on several issues concerning research involving human participants, issuing five reports and numerous recommendations that, when viewed as a whole, reflect our evolving appreciation of the numerous and complex challenges facing the implementation and oversight of any system of protections. The concerns and recommendations addressed in these reports reflect our dual commitment to ensuring the protection of those who volunteer for research while supporting the continued advance of science and understanding of the human condition. This report views the oversight system as a whole, provides a rationale for change, and offers an interrelated set of recommendations to improve the protection of human participants and enable the oversight system to operate more ting research r testing a new medical treatment, interviewing people about their personal habits, studying how people think and feel, or observing how they live within groups, research seeks to learn something new about the human condition. Unfortunately, history has also demonstrated that researchers sometimes treat participants not as persons but as mere objects of study. For over half a century, since the revelations of medical torture under the guise of medical experimentation were described at the nuremberg trials,3 it has been agreed that people should participate in research only when the study addresses important questions, its risks are justifiable, and an individual’s participation is voluntary and principles underlying the belmont report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research (belmont report) (national commission 1979) have served for over 20 years as a leading source of guidance regarding the ethical standards that should govern research with human participants in the united states. The belmont report emphasized that research must respect the autonomy of participants, must be fair in both conception and implementation, and must maximize potential benefits while minimizing possible harms. But although the belmont report is rightly hailed as a key source of guidance on informed consent, assessment of risk, and the injustice of placing individuals (and groups) in situations of vulnerability, the principles the report espouses and the regulations adopted as federal policy 20 years ago have often fallen short in achieving their overarching goal of protecting human research participants. Central protection for research participants is the guarantee that someone other than the investigator will assess the risks of the proposed research. No one should participate in research unless independent review concludes that the risks are reasonable in relation to the potential benefits. In the united states, the institutional review board, or irb, has been the principal structure responsible for conducting such ndent review of research is essential because it improves the likelihood that decisions are made free from inappropriate influences that could distort the central task of evaluating risks and potential benefits. All reviewers who themselves are members of the research community should recognize that their familiarity with research and (perhaps) their predilection to support research are factors that could distort their judgment. Truly independent and sensitive review requires more involvement of individuals drawn from the ranks of potential research participants or those who can adequately represent the interests of potential research participants. When reviewed for risks and potential benefits, research studies must be evaluated in their entirety.

Studies often include different components, however, and the risks and potential benefits of each should also be examined separately, lest the possibility of great benefit or monetary enticement in one component cause potential participants or irbs to minimize or overlook risk in another. No matter what potential benefit is offered to individual participants or society at large, the possibility of benefit from one element of a study should not be used to justify otherwise unacceptable our view, irbs should appreciate that for some components of a study, participants might incur risks with no personal potential benefit, for example, when a nondiagnostic survey is included among the components of a psychotherapy protocol or when placebos are given to some participants in a drug trial. For these elements, there should be some limitation on the amount of social and physical risk that can be imposed, regardless of the participants’ willingness to participate or the monetary (or other) enticement being offered. Further, the possibility of some benefit from one element of a study should not be used to justify otherwise unacceptable elements of research whose potential benefits, if any, accrue, solely to society at large. If removing the risky al bioethics advisory impair the study as a whole, then the entire study should be redesigned so that each of its elements presents risks that are reasonable in relation to potential parts of studies can obscure risks, such as when standard medical interventions are compared in a patient population, leading some participants and researchers to discount the risks because they are associated with known therapies. It is essential that participants and investigators not be led to believe that participating in research is tantamount to being in a traditional therapeutic relationship. Regardless of whether there is the possibility or even the likelihood of direct benefit from participation in research, such participation still alters the relationship between a professional and the participant by introducing another loyalty beyond that to the participant, to wit, loyalty to doing good science. It is too often forgotten that even though the researchers may consider participants’ interests to be important, they also have a serious, and perhaps conflicting, obligation to of experience with the current system of independent review have demonstrated that there are enduring questions about how to arrive at such impartial judgments and how to go about deciding when potential benefits justify risks that are incurred solely by participants or the community from which they come. Irbs are overburdened by the volume of research coming before them, a strain that is compounded by concerns about training of irb members and possible conflicts of interest. In addition, the constantly changing nature of research challenges existing notions about what constitutes risks and potential e irbs are so central to the current oversight system, they need better guidance on how to review and monitor research, how to assess potential benefits to research participants and their communities, and how to distinguish among levels of risk. This report provides such guidance in the following areas: determining the type of review necessary for minimal risk research; ensuring that research participants are able to make voluntary decisions and are appropriately informed prior to giving consent; providing adequate protections for privacy and confidentiality; identifying appropriate measures participants are susceptible to coercion or are otherwise placed in vulnerable situations; and monitoring ongoing research. In addition, the report recommends that irb members and staff complete educational and certification programs on research ethics before being permitted to review research ing voluntary informed when risks are reasonable, however, no one should participate in research without giving voluntary informed consent (except in the case of an appropriate authorized representative or a waiver). Investigators must make appropriate disclosures and ensure that participants have a good understanding of the information and their choices, not only at the time of enrollment, but throughout the ng in this process is one of the best ways researchers can demonstrate their concern and respect for those they aim to enroll in a study. Both the information and the way it is conveyed—while meeting full disclosure requirements—must be tailored to meet the needs of the participants in the particular research context. In addition, documentation requirements must be adapted for varying research settings, and the criteria for deciding when informed consent is not necessary must be clarified so that participants’ rights and welfare are not decision to participate in research must not only be informed, it must be voluntary. Even when risks are reasonable and informed consent is obtained, it may nonetheless be wrong to solicit certain people as participants. Those who are not fully capable of resisting the request to become participants—such as prisoners and other institutionalized or otherwise vulnerable persons—should not be enrolled in studies merely because they are easily accessible or convenient. This historic emphasis on protecting people from being exploited as ipants, however, has failed to anticipate a time when, at least for some areas of medical research, people would be demanding to be included in certain studies because they might provide the only opportunity for receiving medical care for life-threatening research inclusive while protecting individuals categorized as able individuals need additional protection in research. Although certain individuals and populations are more vulnerable as human participants than others, people whose circumstances render them vulnerable should not be arbitrarily excluded from research for this reason alone. Women with small children, who are viewed as less reliable research participants due to conflicting demands on time). It is not their gender or other group designation that exposes them to injury or coercion, but rather their situation that can be exploited by ethically unacceptable research. At other times it is the intrinsic characteristics of the person—for example, children or those with certain mental or developmental disorders—that make them generally vulnerable in the research response, whenever possible, should not be to exclude people from research, but instead to change the research design so that it does not create situations in which people are unnecessarily harmed. To the extent that the results are not generalizable, the potential societal benefits that justify doing the research are attenuated. Whenever possible, research should be designed to encourage the participation of all groups while protecting their rights and accomplish this, we recommend that rather than focusing primarily on categorizing groups as vulnerable, investigators and irbs should also recognize and avoid situations that create susceptibility to harm or coercion. Such situations may be as varied as patients being recruited by their own physicians; sick and desperate patients seeking enrollment in clinical trials; participants being recruited by those who teach or employ them; or studies involving participants with any characteristic that may make them less likely to receive care and respect from others (e. In these circumstances, rather than excluding whole groups of people, researchers should design studies that reduce the risk of exploitation, whether by using a different method of recruitment, by using a recruiter who shares the participants’ characteristics, or by some other technique. It requires researchers to consider carefully their research design and the potential pool of participants. At times, it will mean anticipating that otherwise seemingly benign situations may become more complex because a particular participant or group of participants will be unusually susceptible to harm or manipulation in this situation. At other times, the nature of the vulnerability may require using a different research design. Rather, it acknowledges the full range and realities of the human sating for e all these precautions, however, some research participants might be harmed. Participants who are harmed as a direct result of research should be cared for and compensated.

For those who endure harm while participating in research, it is often very difficult to separate injuries traceable to the research from those that stem from the underlying disease or social condition being studied. For others, appropriate care and compensation would be far beyond the means of the researchers, their sponsors, and their institutions. Two decades ago, al bioethics advisory ent’s commission for the study of ethical problems in medicine and biomedical and behavioral research called for pilot studies of compensation programs—a recommendation that was not pursued. Regardless of individual motives, research participants are providing a service for society, and justice requires that they be treated with great respect and receive appropriate care for any related injuries. It should always be remembered that it is a privilege for any researcher to involve human participants in his or her ishing a comprehensive, effective, and streamlined the united states, government regulations, professional guidelines, and the general principles highlighted in the belmont report (1979) form the basis of the current system of protections. Even today, they apply to most—but not all—research funded or conducted by the federal government, but have inconsistent and sometimes no direct application to research funded or conducted by state governments, foundations, or industry. And they apply to other research only when the investigators and their institutions volunteer to abide by the rules. Comprehensive and effective oversight system is essential to uniformly protect the rights and welfare of participants while permitting ethically and scientifically responsible research to proceed without undue delay. A fundamental flaw in the current oversight system is the ethically indefensible difference in the protection afforded participants in federally sponsored research and those in privately sponsored research that falls outside the jurisdiction of the food and drug administration (fda). This is ipants should be protected from avoidable harm, whether the research is publicly or privately financed. This report, we recommend that the protections of an oversight system extend to the entire private sector for both domestic and international research. A credible, effective oversight system must apply to all research, and all people are entitled to the dignity that comes with freely and knowingly choosing whether to participate in research, as well as to protection from undue research risks. This is consistent with our 1997 resolution that no one should be enrolled in research absent the twin protections of independent review and voluntary informed when current protections apply, the interpretation of the federal regulations can vary unpredictably, depending on which federal agency oversees the research. This has slowed the diffusion of basic protections and made it almost impossible to develop consistent interpretations of the basic protections or those relevant to especially problematic research, such as studies involving children or the decisionally impaired. Nor has there been a unified response to emerging areas of research, such as large-scale work on medical records and social science databases or on stored human biological ’s research protection system cannot react quickly to new developments. Efforts to develop rules for special situations, such as research on those who can no longer make decisions for themselves, have languished for decades in the face of bureaucratic hurdles, and there is no reason to believe that efforts to oversee other emerging research areas will be any more efficient. In addition, the current system leaves people vulnerable to new, virtually uncontrolled experimentation in emerging fields, such as some aspects of reproductive medicine and genetic , some areas of research are not only uncontrolled, they are almost invisible. In an information age, poor management of research using medical records, human tissue, or personal interview data could lead to employment and insurance discrimination, social stigmatization, or even criminal prosecution. The privacy and confidentiality concerns raised by this research are real, but the federal response has often been illusory. The time has come to have a single source of guidance for these emerging areas, one that would be better positioned to effect change across all divisions of the government and private sector, as well as to facilitate development of specialized review bodies, as this report we propose a new independent oversight office that would have clear authority over all other segments of the federal government and extend protections to the entire private sector for both domestic and international research. Although assigning one department, such as the department of health and human services (dhhs), the role of “first among equals” would allow it to advocate forcefully for uniform rules across the government, without special provisions it would not have the authority to require other departments to comply, nor is it certain to escape the temptation to develop rules premised on a traditional, biomedical model rather than the wider range of research to be l research protections should be uniform across all government agencies, academe, and the private sector, but they should be flexible enough to be applied in widely different research settings or to emerging areas of research. Furthermore, any central coordinating body should be open to public input, have significant political or legal authority over research involving human participants—whether in the public or private sector—and have the support of the executive and legislative branches of ion as the key to promoting local tly, federal protections depend on a decentralized oversight system involving irbs, institutions, investigators, sponsors, and participants. We endorse the spirit and intent of this approach, specifically its contention that the ethical obligation to protect participants lies first with researchers, their sponsors, and the irbs that review their research. Protecting research participants is a duty that researchers, research institutions, and sponsors cannot delegate completely to others or to the government. Rather, it is accomplished by acting within a culture of concern and respect for research is unrealistic to think that ethical obligations can be fully met without guidance and resources. To help researchers and irbs fulfill their responsibilities, the federal government should promote the development of education, certification, and accreditation systems that apply to all researchers, all irb members and staff, and all institutions. These tools should help researchers craft and irbs review studies that pose few problems and to know when their work requires special oversight. Today, investigators and irbs are rightly confused over issues as basic as which areas of inquiry should be reviewed and who constitutes a human ion is the foundation of the oversight system and is essential to protecting research participants. In all of our reports, we have highlighted the need to educate all those involved in research with human participants, including the public, investigators, irb members, insti-tutions, and federal agencies. In cloning human beings (1997), we recommended federal support of public education in biomedical sciences that increasingly affect our cultural values. L and policy issues in international research: clinical trials in developing countries (2001), we al bioethics advisory es to help developing countries build their capacity for designing and conducting clinical trials, for reviewing the ethics and science of proposed research, and for using research results after a trial is this report, we again acknowledge the inadequacy of educational programs on research ethics in the united states.

We recommend that investigators and irb members and staff successfully complete educational programs on research ethics and become certified before they perform or review research, that research ethics be taught to the next generation of scientists, and that research ethics be included in continuing education ying the scope of areas of scientific inquiry are “research,” and many of these involve human participants, but only some need federal oversight, while others might be better regulated through professional ethics, social custom, or other state and federal law. For example, certain types of surveys and interviews are considered research, but they can be well managed to avoid harms without federal oversight, as the risks are few and participants are well situated to decide for themselves whether to participate. On the other hand, certain studies of medical records, databases, and discarded surgical tissue are often perceived as something other than human research, even when the information retrieved is traceable to an identifiable person. Such research does need oversight to avoid putting people at risk of identity disclosure or discrimination without their knowledge. Federal policies should clearly identify the kinds of research that are subject to review and the types of research participants to whom protections should apply. When research poses significant risks or when its risks are imposed on participants without their knowledge, it clearly requires oversight. However, meaningless or overly rigid oversight engenders disdain on the part of researchers, creates an impossible and pointless workload for irbs, and deters ethically sound research from going ng that the level of review corresponds to the level of within areas of research that need oversight, many individual studies will involve little or no risk to participants. Although current federal policies allow for some distinction between research involving minimal risk and research involving more than minimal risk, the distinction operates mostly in terms of how the research will be reviewed—that is, how procedures are to be followed. But the distinction should be based on how the research is pursued, how the participants are treated, and how the work is monitored over time. Overall, the emphasis should be on knowing how to protect participants rather than on knowing how to navigate research regulations. Instead of focusing so much on the period during which a research design is reviewed, oversight should also include an ongoing system of education and certification that helps researchers to anticipate and minimize research risks. Oversight should also make it easier for researchers to collaborate with their colleagues here and abroad without the burden of redundant ch review and monitoring should be intensified as the risk and complexity of the research at all times should emphasize protecting participants rather than following rigid rules. In addition, the review process should facilitate rather than hinder collaborative research among institutions and across national boundaries, provided that participants are ing resources for the oversight ng a system that protects the rights and welfare of participants and facilitates responsible research demands political and financial support from the federal government as well as the presence of a central coordinating body to provide guidance and oversee education and accreditation efforts. The oversight system should be adequately funded at all levels to ensure that research continues in a manner that demonstrates respect and concern for the interests of research al bioethics advisory y of report proposes 30 recommendations for changing the oversight system at the national and local levels to ensure that all research participants receive the appropriate protections. The adoption of these recommendations, which are directed at all who are involved in the research enterprise, will not only lead to better protection for the participants of research, but will also serve to promote ethically sound research while reducing unnecessary bureaucratic burdens. Achieving these goals will, in turn, restore the respect of investigators for the system used to oversee research, support the public’s trust in the research enterprise, and enhance public enthusiasm for all research involving human and structure of the oversight entitlements due to all research participants of a prior independent review of risks and potential benefits and the opportunity to exercise voluntary informed consent are the most basic and essential protections for all research participants. However, not all research participants receive these entitlements and not all are protected by the existing oversight system. The commitment to protect participants should not be voluntary, nor should requirements be in place for only some human research. Extending current protections to all research, ly or privately funded, and making uniform all federal regulations and guidance cannot be accomplished within the current oversight system, in which no entity has the authority to act on behalf of all research participants. Thus, to facilitate the extension of the same protections to all humans participating in research, a unified, comprehensive federal policy promulgated and interpreted by a single office is endation 2. The federal oversight system should protect the rights and welfare of human research participants by requiring 1) independent review of risks and potential benefits and 2) voluntary informed consent. To ensure the protection of the rights and welfare of all research participants, federal legislation should be enacted to create a single, independent federal office, the national office for human research oversight (nohro), to lead and coordinate the oversight system. A unified, comprehensive federal policy embodied in a single set of regulations and guidance should be created that would apply to all types of research involving human participants (see recommendation 2. Whether particular research activities involving human participants should be subject to a federal oversight system has been a source of confusion for some time. No regulatory definition of covered research can be provided that has the sensitivity and specificity required to ensure that all research activities that include human participants that should be subject to oversight are always included and all activities that should be excluded from oversight protections are always excluded. Clarification and interpretation of the definition of what constitutes research involving human participants al bioethics advisory ably be required if the oversight system is to work effectively and efficiently. Moreover, there will always be cases over which experts disagree about the research status of a particular activity. One of the important leadership roles the proposed oversight office should fulfill is that of providing guidance on determining whether an activity is research involving human participants and is therefore subject to endation 2. Federal policy should cover research involving human participants that entails systematic collection or analysis of data with the intent to generate new knowledge. Research should be considered to involve human participants when individuals 1) are exposed to manipulations, interventions, observations, or other types of interactions with investigators or 2) are identifiable through research using biological materials, medical and other records, or databases. Federal policy also should identify those research activities that are not subject to federal oversight and outline a procedure for determining whether a particular study is or is not covered by the oversight proposed federal office should initiate a process in which representatives from various disciplines and professions (e.

Social science, humanities, business, public health, and health services) contribute to the development of the definition and the list of research activities subject to the oversight gh the definition of research involving human participants should be applied to all disciplines, the risks differ both qualitatively and quantitatively across the spectrum of research. Therefore, the oversight system should ensure that all covered research is subject to basic protections—such as a process of informed consent—with the exceptions of the specified conditions for which these protections can be waived, including protection of privacy and confidentiality and minimization of risks. Because the proposed oversight system may include more research activities, it is more critical than ever that review mechanisms and criteria for various types ch are suited to the nature of the research and the likely risks involved. More specific guidance is needed for review of different types of research, including appropriate review criteria and irb composition. For example, procedures other than full board review could be used for minimal risk research, and national level reviews could supplement local irb review of research involving novel or controversial ethical endation 2. Federal policy should require research ethics review that is commensurate with the nature and level of risk involved. Standards and procedures for review should distinguish between research that poses minimal risk and research that poses more than minimal risk. In addition, the federal government should facilitate the creation of special, supplementary review bodies for research that involves novel or controversial ethical ion, certification, and ting the rights and welfare of research participants is the major ethical obligation of all parties involved in the oversight system, and to provide these protections, all parties must be able to demonstrate competence in research ethics—that is, conducting, reviewing, or overseeing research involving human participants in an ethically sound manner. Such competence entails not only being knowledgeable about relevant research ethics issues and federal policies, but also being able to identify, disclose, and manage conflicting interests for institutions, investigators, or irbs. All institutions and sponsors engaged in research involving human participants should provide educational programs in research ethics to appropriate institutional officials, investigators, institutional review board members,And institutional review board staff. Among other issues, these programs should emphasize the obligations of institutions, sponsors, institutional review boards, and investigators to protect the rights and welfare of participants. Colleges and universities should include research ethics in curricula related to research methods, and professional societies should include research ethics in their continuing education endation 3. The federal government, in partnership with academic and professional societies, should enhance research ethics education related to protecting human research participants and stimulate the development of innovative educational programs. Professional societies should be consulted so that educational programs are designed to meet the needs of all who conduct and review ing all parties in research ethics and human participant protections is effective only when it results in the necessary competence for designing and conducting ethically sound research, including analyzing, interpreting, and disseminating results in an ethically sound manner. As the complexion of research continues to change and as technology advances, new and challenging ethical dilemmas will emerge. And, as more people become involved in research as investigators or in roles that are specifically related to oversight, it becomes increasingly important for all parties to be able to demonstrate competence in the ethics of research involving human gh accreditation and certification do not always guarantee the desired outcomes, these programs, which generally involve experts and peers developing a set of standards that represents a consensus of best practices, can be helpful in improving performance. All investigators, institutional review board members, and institutional review board staff should be certified prior to conducting or reviewing research involving human participants. Sponsors, institutions, and independent institutional review boards should be accredited in order to conduct or review research involving human participants. Assessing the behavior of investigators is an important part of protecting research participants and should be taken seriously as a responsibility of each institution. Investigators, irbs, and institutions should discuss the many practical issues involved in monitoring investigators as they conduct their research studies and provide input into the regulatory endation 3. The process for assuring compliance with federal policy should be modified to reduce any unnecessary burden on al bioethics advisory ting research and to register institutions and institutional review boards with the federal government. Research setting that involves human participants necessarily creates a conflict of interest for investigators who seek to develop or revise knowledge by enrolling individuals in research protocols to obtain that knowledge. Overzealous pursuit of scientific results could lead to harm if, for example, investigators design research studies that pose unacceptable risks to participants, enroll participants who should not be enrolled, or continue studies even when results suggest they should have been modified or halted. Conflicts of interest can also exist for irb members or the institutions in which the research will be conducted. Thus, it is important to address prospectively the potentially harmful effects on participants that conflicts of interest might zations, particularly academic institutions, should become more actively involved in managing investigators’ and irb members’ conflicts of interest and increase their efforts for self-regulation in this arena. Irb review of research studies is one method for identifying and dealing with conflicts of interest that might face investigators. By having irbs review research studies prospectively and follow an irb-approved protocol, investigators and irbs together can manage conflict between the investigators’ desire to advance scientific knowledge and to protect the rights and welfare of research participants. Financial and other obvious conflicts for irb members, such as collaboration in a research study, are often less difficult to identify and manage than some of the more subtle and pervasive ce should be developed to assist irbs in identifying various types of endation 3. Federal policy should define institutional, institutional review board, and investigator conflicts of interest, and guidance should be issued to ensure that the rights and welfare of research participants are endation 3. Policies also should describe specific types of prohibited riate composition of irb membership ensures that research studies are reviewed with the utmost regard for protecting the rights and welfare of research participants. In addition, unaffiliated members do not have to be present for an irb to conduct review and approve research studies.

Thus, irbs can approve research with only institutional representation present as long as a nonscientist and a quorum are also present. Irbs should strive to complement their membership by having clearly recognizable members who are unaffiliated with the institutions, members who are nonscientists, and members who represent ctives of participants. The distribution of institutional review board members with relevant expertise and experience should be commensurate with the types of research reviewed by the institutional review board (see recommendation 3. Institutional review boards should include members who represent the perspectives of participants, members who are unaffiliated with the institution, and members whose primary concerns are in nonscientific areas. For assessing risks and potential addition to protecting the rights and welfare of research participants, it is equally important to protect them from avoidable harm. Thus, an irb’s assessment of the risks and potential benefits of research is central to determining whether a research study is ethically acceptable. Yet, this assessment can be a difficult one to make, as there are no clear criteria for irbs to use in judging whether the risks of research are reasonable in terms of what might be gained by the individual or should be able to identify whether a clear and direct benefit to society or the research participants might result from participating in the study. In fact, if it is not clear that a procedure also offers the prospect of direct benefit, irbs should treat the procedure as one solely designed to answer the research question(s). A major advantage of this approach is that it avoids justifying the risks of procedures that are designed solely to answer the research question(s) based on the likelihood that another procedure in the protocol would provide a endation 4. An analysis of the risks and potential benefits of study components should be applied to all types of covered research (see recommendation 2. In general, each component of a study should be evaluated separately, and its risks should be both reasonable in themselves as well as justified by the potential benefits to society or the participants. Potential benefits from one component of a study should not be used to justify risks posed by a separate component of a ining whether a study poses more than minimal risk is a central ethical and procedural function of the irb. I)) provides an ambiguous standard by which risks involved in a research study are compared to those encountered al bioethics advisory life. However, it is unclear whether this applies to those risks found in the daily lives of healthy individuals or those of individuals who belong to the group targeted by the research. If it refers to the individuals to be involved in the research, then the same intervention could be classified as minimal risk or greater than minimal risk, depending on the health status of those participants and their particular experiences. Thus, research would involve no more than minimal risk when it is judged that the level of risk is no greater than that encountered in the daily lives of the general endation 4. Federal policy should distinguish between research studies that pose minimal risk and those that pose more than minimal risk (see recommendation 2. If a study that would normally be considered minimal risk for the general population nonetheless poses higher risk for any prospective participants, then the institutional review board should approve the study only if it has determined that appropriate protections are in place for all prospective ting segments of society should have the opportunity to participate in research, if they wish to do so and if they are considered to be appropriate participants for a given protocol. However, some individuals may need additional protections before they can fully participate in the research study; otherwise they might be more coercion or exploitation. Once safeguards are established, investigators should not exclude persons categorized as vulnerable from research involving greater than minimal risk because this would deprive them of whatever potential direct benefits they might receive from the research and deprive their communities and society from the benefit of the knowledge such research might endation 4. Guidance should be developed on how to identify and avoid situations that render some participants or groups vulnerable to harm or coercion. Sponsors and investigators should design research that incorporates appropriate safeguards to protect all prospective izing the informed consent than focusing on the ethical standard of informed consent and what is entailed in the process of obtaining informed consent, irbs and investigators have followed the lead of the federal regulations and have tended to focus on the disclosures found in the consent form. Informed consent should be an active process through which both parties share information and during which the participant at any time can freely decide whether to withdraw from or continue to participate in the research. It is time to place the emphasis process of informed consent to ensure that information is fully disclosed, that competent participants fully understand the research in order to make informed choices, and that decisions to participate or not are always made endation 5. Federal policy should emphasize the process of informed consent rather than the form of its documentation and should ensure that competent participants have given their voluntary informed consent. Guidance should be issued about how to provide appropriate information to prospective research participants, how to promote prospective participants’ comprehension of such information, and how to ensure that participants continue to make informed and voluntary decisions throughout their involvement in the of informed ing voluntary informed consent should not be a requirement for every research study. In fact, waiving the informed consent process is justifiable in research studies that include no interaction between investigators and participants, such as in studies using existing identifiable data (e. In these kinds of research, risks are likely to arise from the acquisition, use, or dissemination of information resulting from the study and are likely to involve threats to privacy and breaches in confidentiality. Some studies using existing identifiable data or some observational studies) to waive informed consent requirements if all of the following criteria are met:A) all components of the study involve minimal risk or any component involving more than minimal risk must also offer the prospect of direct benefit to participants;. The waiver is not otherwise prohibited by state, federal, or international law; c) there is an adequate plan to protect the confidentiality of the data; d) there is an adequate plan for contacting participants with information derived from the research, should the need arise; and e) in analyzing risks and potential benefits, the institutional review board specifically determines that the benefits from the knowledge to be gained from the research study outweigh any dignitary harm associated with not seeking informed ntation of informed gh the federal regulations may have been intended to reflect a legal standard for documentation of informed consent, nbac is aware of no case law in which a signed, written consent form is required. To fulfill the substantive ethical standard of informed consent, depending on the type of research proposed, it may be more appropriate to use other forms of documentation, such as audiotape, videotape, witnesses, or telephone calls to participants verifying informed consent and participation in the research endation 5.

Especially when individuals can easily refuse or discontinue participation, or when signed forms might threaten confidentiality, institutional review boards should permit investigators to use other means of verifying that informed consent has been ting privacy and y and confidentiality are complex and poorly understood concepts in the context of some research. Because privacy concerns vary by type and context of research and the culture and individual circumstances of participants, investigators should be well informed al bioethics advisory l of the cultural norms of the participants. In addition, investigators should be aware of the various research procedures and methods that can be used to respect privacy. Needed is a clear, comprehensive reg-ulatory definition of privacy along with guidance for protecting privacy in various types of privacy concerns, concerns about confidentiality vary by the type and context of the research. No one set of procedures can be developed to protect confidentiality in all research contexts. Thus, irbs and investigators must tailor confidentiality protections to the specific circumstances and methods used in each specific research study. The feasibility of additional mechanisms should be examined to strengthen confidentiality protections in research ring of ongoing ual review and monitoring of research that is in progress is a critical element of the oversight system. The frequency and need for continuing review vary depending on the nature of research, with some protocols not requiring continuing review. In research involving high or unknown risks, the first few trials of a new intervention may substantially affect known about the risks and potential benefits of that intervention. Even if the knowledge does not warrant changes in study design, it may warrant changes in the information presented to prospective and enrolled the other hand, the ethics issues and participant protections necessary in minimal risk research are unlikely to be affected by developments from within or outside the research—for example, research involving the use of existing data or research that will no longer involve contact with participants because it is in the data analysis phase. Continuing review of such research should not be required because it is unlikely to provide any additional protection to research participants and merely increases the burden of irbs. However, because minimal risk research does involve some risk, irbs may choose to require continuing review. Clarifying the nature of the continuing review requirements would allow irbs to better focus their efforts on reviewing riskier research and would increase protections for participants where they are most endation 6. Federal policy should describe clearly the requirements for continuing institutional review board review of ongoing research. Continuing review should not be required for research studies involving minimal risk, research involving the use of existing data, or research that is in the data analysis phase when there is no additional contact with participants. Federal policy should clarify when changes in research design or context require review and new approval by an institutional review e event ing adverse events reports can be a major burden for irbs and investigators because of the high volume and ambiguous nature of such events and the complexity of the pertinent regulatory requirements. The federal government should create a uniform system for reporting and evaluating adverse events occurring in research, especially in multi-site research. The primary concern of the reporting system should be to protect current and prospective research of cooperative or multi-site research of the greatest burdens on irbs and investigators is the review of multi-site studies. Requiring multiple institutions to review the same protocol is unnecessarily taxing and provides no additional protection to participants. In addition, such review poses problems in the initial stages of review as well as in the continual review and monitoring stages and is especially problematic in the evaluation of adverse events in clinical tive and creative alternative mechanisms and processes for reviewing protocols in multi-site research are needed. For multi-site research, federal policy should permit central or lead institutional review board review, provided that participants’ rights and welfare are rigorously sation for research-related ipants who volunteer to be in a research study and are harmed as a direct result of that study should be cared for and compensated. However, no adequate database exists that describes the number of injuries or illnesses that are suffered by research participants, the proportion of these illnesses or injuries that are caused by the research, and the medical treatment and rehabilitation expenses that are subsequently borne by the participants. It may be argued that regardless of the magnitude of the problem, the costs of research injuries should never be borne by participants. At this time, injured research participants alone bear both the cost of lost health and the expense of medical care, unless they have adequate health insurance or successfully pursue legal action to gain compensation from the specific individuals or organizations that were involved in conducting the research. Comprehensive system of oversight of human research should include a mechanism to compensate participants for medical and rehabilitative costs resulting from research-related al bioethics advisory endation 6. The federal government should study the issue of research-related injuries to determine if there is a need for a compensation program. If needed, the federal government should implement the recommendation of the president’s commission for the study of ethical problems in medicine and biomedical and behavioral research (1982) to conduct a pilot study to evaluate possible program need for ng the recommendations made in this report will generate additional costs for institutions, sponsors, and the federal government (through the establishment of a new federal oversight office). Sponsors of research, whether public or private, should work together with institutions carrying out the research to make the necessary funds endation 7. The proposed oversight system should have adequate resources to ensure its effectiveness and ultimate success in protecting research participants and promoting research:A) funds should be appropriated to carry out the functions of the proposed federal oversight office as outlined in this report. B) federal appropriations for research programs should include a separate allocation for oversight activities related to the protection of human participants. D) federal agencies, other sponsors, and institutions should make additional funds available for oversight report raises many questions about ethical issues that cannot be answered because of insufficient or nonexistent empirical evidence.

Current thinking about ethical issues in research—such as analysis of risks ial benefits, informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, and vulnerability—would greatly benefit from additional research. Deserving of more study, for example, are questions regarding the development of effective approaches for assessing cognitive capacity, for evaluating what participants want to know about research, and for determining how to ascertain best practices for seeking informed consent. In general, understanding the ethical conduct of research would be advanced by increased interdisciplinary discussion that would include biomedical and social scientists, lawyers, and endation 7. The federal government, in partnership with academic institutions and professional societies, should facilitate discussion about emerging human research protection issues and develop a research agenda that addresses issues related to research ethics. For example, the office for human research protections is implementing a new process by which institutions assure future compliance with human participant protections. Public responsibility in medicine and research has established training programs and has co-founded a new organization, the association for the accreditation of human research protection programs. Nbac 1997), research involving persons with mental disorders that may affect decisionmaking capacity (nbac 1998), ethical issues in human stem cell research (nbac 1999a), research involving human biological materials: ethical issues and policy guidance (nbac 1999b), and ethical and policy issues in international research: clinical trials in developing countries (nbac 2001). There are, of course, some circumstances in which consent cannot be obtained and in which an overly rigid adherence to this principle would preclude research that is either benign or potentially needed by the participant him- or herself. Thus, nbac endorses the current exceptions for research that is of minimal risk to participants and for potentially beneficial research in emergency settings where no better alternative for the participants exists. Nbac also urges attention to emerging areas of record, database, and tissue bank research in which consent serves only as a sign of respect and in which alternative ways to respect participants do exist (nbac 1999b; 21 cfr 50. Government printing al commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral research (national commission). Department of health & human ance & er irbs & obtain home > ohrp > regulations & policy > the belmont tionshas sub items, regulations45 cfr cehas sub items, guidancefrequently asked questions45 cfr 46 nce process en: research with children research determination ed consent igator responsibilities registration process er research y improvement activities able ical materials & ts for tions & policy archived belmont reportoffice of the l principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of national commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral : department of health, education, and : notice of report for public y: on july 12, 1974, the national research act (pub. 93-348) was signed into law, there-by creating the national commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral research. One of the charges to the commission was to identify the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects and to develop guidelines which should be followed to assure that such research is conducted in accordance with those principles. In carrying out the above, the commission was directed to consider: (i) the boundaries between biomedical and behavioral research and the accepted and routine practice of medicine, (ii) the role of assessment of risk-benefit criteria in the determination of the appropriateness of research involving human subjects, (iii) appropriate guidelines for the selection of human subjects for participation in such research and (iv) the nature and definition of informed consent in various research belmont report attempts to summarize the basic ethical principles identified by the commission in the course of its deliberations. It is a statement of basic ethical principles and guidelines that should assist in resolving the ethical problems that surround the conduct of research with human subjects. The department requests public comment on this al commission for the protection of human subjects of biomedical and behavioral s of the h john ryan, m. Attorney, vombaur, coburn, simmons & turtle, washington, l principles and guidelines for research involving human subjects. Basic ethical ment of risk and ion of l principles & guidelines for research involving human ific research has produced substantial social benefits. Public attention was drawn to these questions by reported abuses of human subjects in biomedical experiments, especially during the second world war. This code became the prototype of many later codes[1] intended to assure that research involving human subjects would be carried out in an ethical codes consist of rules, some general, others specific, that guide the investigators or the reviewers of research in their work. Broader ethical principles will provide a basis on which specific rules may be formulated, criticized and principles, or general prescriptive judgments, that are relevant to research involving human subjects are identified in this statement. These three are comprehensive, however, and are stated at a level of generalization that should assist scientists, subjects, reviewers and interested citizens to understand the ethical issues inherent in research involving human subjects. These principles cannot always be applied so as to resolve beyond dispute particular ethical problems. The objective is to provide an analytical framework that will guide the resolution of ethical problems arising from research involving human statement consists of a distinction between research and practice, a discussion of the three basic ethical principles, and remarks about the application of these principles. Boundaries between practice and is important to distinguish between biomedical and behavioral research, on the one hand, and the practice of accepted therapy on the other, in order to know what activities ought to undergo review for the protection of human subjects of research. The distinction between research and practice is blurred partly because both often occur together (as in research designed to evaluate a therapy) and partly because notable departures from standard practice are often called "experimental" when the terms "experimental" and "research" are not carefully the most part, the term "practice" refers to interventions that are designed solely to enhance the well-being of an individual patient or client and that have a reasonable expectation of success. By contrast, the term "research' designates an activity designed to test an hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships). Research is usually described in a formal protocol that sets forth an objective and a set of procedures designed to reach that a clinician departs in a significant way from standard or accepted practice, the innovation does not, in and of itself, constitute research. The fact that a procedure is "experimental," in the sense of new, untested or different, does not automatically place it in the category of research. Radically new procedures of this description should, however, be made the object of formal research at an early stage in order to determine whether they are safe and effective.

Thus, it is the responsibility of medical practice committees, for example, to insist that a major innovation be incorporated into a formal research project [3]. And practice may be carried on together when research is designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a therapy. This need not cause any confusion regarding whether or not the activity requires review; the general rule is that if there is any element of research in an activity, that activity should undergo review for the protection of human b: basic ethical principles. Basic ethical expression "basic ethical principles" refers to those general judgments that serve as a basic justification for the many particular ethical prescriptions and evaluations of human actions. Three basic principles, among those generally accepted in our cultural tradition, are particularly relevant to the ethics of research involving human subjects: the principles of respect of persons, beneficence and justice. Respect for persons incorporates at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. To show lack of respect for an autonomous agent is to repudiate that person's considered judgments, to deny an individual the freedom to act on those considered judgments, or to withhold information necessary to make a considered judgment, when there are no compelling reasons to do r, not every human being is capable of self-determination. The judgment that any individual lacks autonomy should be periodically reevaluated and will vary in different most cases of research involving human subjects, respect for persons demands that subjects enter into the research voluntarily and with adequate information. On the one hand, it would seem that the principle of respect for persons requires that prisoners not be deprived of the opportunity to volunteer for research. On the other hand, under prison conditions they may be subtly coerced or unduly influenced to engage in research activities for which they would not otherwise volunteer. Persons are treated in an ethical manner not only by respecting their decisions and protecting them from harm, but also by making efforts to secure their well-being. Claude bernard extended it to the realm of research, saying that one should not injure one person regardless of the benefits that might come to others. The problem posed by these imperatives is to decide when it is justifiable to seek certain benefits despite the risks involved, and when the benefits should be foregone because of the obligations of beneficence affect both individual investigators and society at large, because they extend both to particular research projects and to the entire enterprise of research. In the case of particular projects, investigators and members of their institutions are obliged to give forethought to the maximization of benefits and the reduction of risk that might occur from the research investigation. In the case of scientific research in general, members of the larger society are obliged to recognize the longer term benefits and risks that may result from the improvement of knowledge and from the development of novel medical, psychotherapeutic, and social principle of beneficence often occupies a well-defined justifying role in many areas of research involving human subjects. Effective ways of treating childhood diseases and fostering healthy development are benefits that serve to justify research involving children -- even when individual research subjects are not direct beneficiaries. Research also makes it possible to avoid the harm that may result from the application of previously accepted routine practices that on closer investigation turn out to be dangerous. A difficult ethical problem remains, for example, about research that presents more than minimal risk without immediate prospect of direct benefit to the children involved. Some have argued that such research is inadmissible, while others have pointed out that this limit would rule out much research promising great benefit to children in the future. However, they are foreshadowed even in the earliest reflections on the ethics of research involving human subjects. For example, during the 19th and early 20th centuries the burdens of serving as research subjects fell largely upon poor ward patients, while the benefits of improved medical care flowed primarily to private patients. Subsequently, the exploitation of unwilling prisoners as research subjects in nazi concentration camps was condemned as a particularly flagrant injustice. These subjects were deprived of demonstrably effective treatment in order not to interrupt the project, long after such treatment became generally t this historical background, it can be seen how conceptions of justice are relevant to research involving human subjects. For example, the selection of research subjects needs to be scrutinized in order to determine whether some classes (e. Finally, whenever research supported by public funds leads to the development of therapeutic devices and procedures, justice demands both that these not provide advantages only to those who can afford them and that such research should not unduly involve persons from groups unlikely to be among the beneficiaries of subsequent applications of the ations of the general principles to the conduct of research leads to consideration of the following requirements: informed consent, risk/benefit assessment, and the selection of subjects of research. Most codes of research establish specific items for disclosure intended to assure that subjects are given sufficient information. These items generally include: the research procedure, their purposes, risks and anticipated benefits, alternative procedures (where therapy is involved), and a statement offering the subject the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw at any time from the research. Additional items have been proposed, including how subjects are selected, the person responsible for the research, r, a simple listing of items does not answer the question of what the standard should be for judging how much and what sort of information should be provided. One standard frequently invoked in medical practice, namely the information commonly provided by practitioners in the field or in the locale, is inadequate since research takes place precisely when a common understanding does not exist. This, too, seems insufficient since the research subject, being in essence a volunteer, may wish to know considerably more about risks gratuitously undertaken than do patients who deliver themselves into the hand of a clinician for needed care. Special problem of consent arises where informing subjects of some pertinent aspect of the research is likely to impair the validity of the research.